A worth reading book review, I Am Beggar Of The World, by Malik Kenan on collection of Afghan folk poetry, mostly composed by women expressing their repressed raw feelings.

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

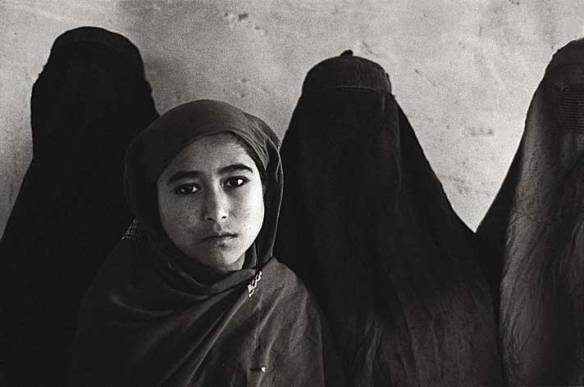

Afghanistan is a nation with a fine poetical tradition reaching back centuries, a tradition in which high literary forms, especially those that derive from Persian or Arabic, are revered. I Am a Beggar of the World is, however, a collection of landays, folk rather than high poetry, an oral tradition created by and for mostly illiterate people, especially women. Traditionally, landays are sung aloud, often to the beat of a hand drum, which, along with other kinds of music, was banned by the Taliban.

A landay has only a few formal properties. Each has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line, thirteen in the second. Sometimes they rhyme, but more often not. The landays in I Am a Beggar of the Worldwere collected by American poet and writer Eliza Griswold. In a 2012 essay in the New York Times, Griswold described the meaning and significance of the form:

Pashtun poetry has long been a form of rebellion for Afghan women, belying the notion that they are submissive or defeated. Landay means ‘short, poisonous snake’ in Pashto, a language spoken on both sides of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. The word also refers to two-line folk poems that can be just as lethal. Funny, sexy, raging, tragic, landay are safe because they are collective. No single person writes a landay; a woman repeats one, shares one. It is hers and not hers. Although men do recite them, almost all are cast in the voices of women. ‘Landay belong to women’, Safia Siddiqi, a renowned Pashtun poet and former Afghan parliamentarian, said. ‘In Afghanistan, poetry is the women’s movement from the inside.’

Traditionally, landay have dealt with love and grief. They often railed against the bondage of forced marriage with wry, anatomical humor… But they have also taken on war, exile and Afghan independence with ferocity… More recently, landay have taken on the Russian occupation, the hypocrisy of the Taliban and the American military presence.

Like most folk literature, Griswold observes, ‘landay can be sorrowful or bawdy. Imagine the Wife of Bath riding through the Himalayan foothills and uttering landay so ribald that they curled the toes of her fellow travelers’.

The drones have come to the Afghan sky.

The mouths of our rockets will sound in reply.

Come to Guantánamo.

Follow the clang of my chains.

May God destroy the Taliban and end their wars.

They’ve made Afghan women widows and whores.

Wormwood grows on the one-eyed Mullah’s grave.

The Talib boys fight blindly on, believing he’s alive.

Hamid Karzai came to Kabul

to teach our girls to dress in Dollars.

I dream I am the president.

When I awake, I am the beggar of the world.

Griswold started collecting landays after learning the story of Rahila Muska, a young woman who, like many in rural Afghanistan, was forbidden from leaving her home. ‘Fearing that she’d be kidnapped or raped by warlords’, Griswold writes in an essay introducing the new collection, ‘her father pulled her out of school after the fifth grade. Poetry, which she learned from other women and on the radio, became her only form of education’:

These days, for women, poetry programs on the radio are one of the few permissible forms of access to the outside world. Such was the case for Rahila Muska, who learned about a women’s literary group called Mirman Baheer via the radio. The group meets in the capital of Kabul every Saturday afternoon; it also runs a phone hotline for girls from the provinces, like Muska, to call in with their own work or to talk to fellow poets. Muska, which means smile in Pashto, phoned in so frequently and showed such promise that she became the darling of the literary circle. She alluded to family problems that she refused to discuss.

One day in the spring of 2010, Muska phoned her fellow poets from a hospital bed in the southeastern city of Kandahar to say that she’d set herself on fire. She’d burned herself in protest. Her brothers had beaten her badly after discovering her writing poems. Poetry — especially love poetry — is forbidden to many of Afghanistan’s women: it implies dishonor and free will. Both are unsavory for women in traditional Afghan culture. Soon after, Muska died.

Griswold travelled to Afghanistan with the photographer Seamus Murphy on an assignment for theNew York Times Magazine ‘to piece together what I could of [Muska’s] brief life story’:

Finding Muska’s family seemed an impossible task — one dead teenage poet writing under the safety of a pseudonym in a war zone — but eventually, with the aid of a highly-effective Pashtun organization called Wadan, the Welfare Association for the Development of Afghanistan, we were able to locate her village and find her parents. Her real name, it turned out, was Zarmina, and her story was about more than poetry.

This was a love story gone awry. Engaged at an early age to her cousin, she’d been forbidden from marrying him, because after the recent death of his father, he couldn’t afford the volver, the bride price. Her love was doomed and her future uncertain; death became the one control she could assert over her life.

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

Although she didn’t write this poem, Rahila Muska often recited landays over the phone to the women of Mirman Baheer. This is common: of the tens of thousands of landays in circulation, the handful a woman remembers relate to her life. Landays survive because they belong to no one. Unlike her notebooks, the little poem couldn’t be ripped up and destroyed by Muska’s father.

http://kenanmalik.wordpress.com/2014/04/20/i-am-the-beggar-of-the-world/